It was an unsettling experience.

Every minute or so, the police would stop their van, jump out and – as people around them began to shout and run away – start to chase citizens more or less at random, it seemed to me, before shoving one or two of them into the back of their vehicle.

One woman wasn’t wearing a mask, an officer explained.

Another might have been selling contraband cigarettes.

Several people had, perhaps, been standing too close together, although it was hard to tell in the dark. And so on.

Lack of trust in the state

The whole process felt arbitrary and alarming – a clear abuse of authority.

But in the days since then I’ve begun to think of that night in Alexandra in a different way; to consider not the police’s behaviour, but rather the hard-learned reactions of the citizens of the township.

To run. And then, if caught, to submit meekly.

It was, I think, a very clear expression of vulnerability – the behaviour of people who feel, instinctively, powerless to challenge the might of the state.

I’ve seen it often, both here in South Africa and – to a far greater extent – in other parts of the continent.

Something similar applies to hospitals too.

I’ve heard – first and second hand – too many anecdotes about people whose relatives were admitted to underfunded public hospital with “a stomach ache” or “just a cold” and who were abruptly pronounced dead within days.

In other words, many people have learned to look towards the police and the medical profession not for salvation, but for something more nuanced.

The smart newsletters

Subscribe to smartly curated newsletters from The Bloomgist

It strikes me that an acute sense of vulnerability – not unique to Africa, of course – has characterised this continent’s response to the pandemic too.

Yes, there was some bluster in the early days about Africa perhaps being spared – and we still hear populists like Tanzania’s President John Magufuli trying to play down the threat.

But most people I’ve spoken to, particularly in poorer neighbourhoods, have shown an increasingly intense and proactive determination to do all they can to protect themselves and their families, and – importantly – not to expect, or rely on, the state to do it for them.

In a sense, that same vulnerable mindset applies to most African governments too.

Africa acted fast and decisively

After all, this is a continent where tuberculosis (TB), HIV, malaria and dysentery still kill – despite impressive recent improvements in public health – millions of people each year.

Six main causes of death in Africa

- 1) Lower respiratory infections (10.4% of deaths):916,851

- 2) HIV/Aids (8.1%):718,800

- 3) Diarrhoeal diseases (7.4%):652,791

- 4) Ischaemic heart disease (5.8%):511,916

- 5) Malaria (4.6%)408,125

- 6) TB (4.6%):405,496

Source: WHO – figures from 2016

And so, governments across the continent are already hard-wired to respond to new public health challenges like Ebola or Covid-19.

That is why they didn’t dither in the early stages of the outbreak.

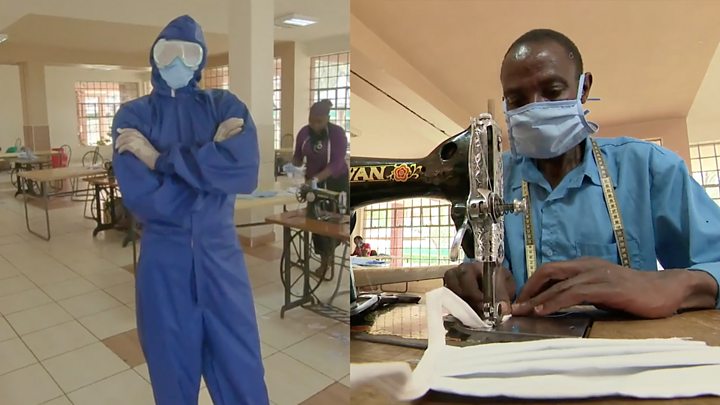

As other countries dabbled with herd immunity, kept their airports wide open, or merely encouraged their citizens to avoid the pub, African states were busy implementing strict lockdowns and re-training their vast standing armies of community health workers.

Delayed but not contained?

But the question now – for South Africa and for the rest of the continent – is whether that sense of vulnerability can help to sustain a much longer and effective fight against the virus because the evidence – from Nigeria to South Sudan and beyond – now appears to show that Africa’s early successes may simply (and usefully) have delayed, rather than contained, Covid-19.

The latest expert projections from a team here in Johannesburg indicate that the virus will – despite an impressively lowered infection curve – still kill more than 40,000 South Africans and is likely to peak only at some point in the second half of July.

At the same time, the severe economic damage caused by the early lockdowns is beginning to test the patience and the coping mechanisms of communities and governments which lack the deep pockets of Western nations.

Some excruciatingly difficult choices and battles lie ahead.

This is not to “catastrophise” Africa.

The continent’s early response – fuelled by a well-honed sense of vulnerability – has been world-class”

Andrew Harding

Africa correspondent, BBC News

The outside world sometimes seems to have flip-flopped – when it has even taken the time to notice – between seeing this continent as a slow-motion disaster that will eclipse all others with its coronavirus horrors, or a place where humidity, sunshine, a young population, widespread TB vaccines, or other less benign tropes, will somehow produce a miracle.

The truth is surely more mundane.

Africa is busy adapting to yet another deadly disease.

Like other parts of the world, it will struggle, and it will eventually prevail, or at least find some sustainable long-term accommodation with the virus.

The continent’s early response – fuelled by a well-honed sense of vulnerability – has been world-class.

But its healthcare systems have been weakened, many would argue, not just by poverty and corruption, but by the systematic luring of African medical staff to Western nations over decades, by the short-termism at the heart of much international aid, and by the power-imbalances at the heart of the global economy and its key institutions.